WIENER WERKSTÄTTE TEXTILES

Heron by Carl Otto Czeschka for Wiener Werkstätte, block printed silk, 1910-11. Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museums

Left: printed silk designed by Maria Likarz-Strauss, 1924. Image courtesy of MAK. Right: design for Fidelio in gouache by Maria Likarz-Strauss, c.1928. Image courtesy of Cooper Hewitt.

It’s hard to overstate the influence that the Wiener Werkstätte exerted on design and decorative arts in the 20th century. The Wiener Werkstätte (which translates as the Vienna Workshop) was an alliance of progressive artist-craftspeople that challenged the accepted trends in mass-produced design at the turn of the century.

The workshop was initially founded in 1903 by Austrian architect Josef Hoffmann and painter Koloman Moser with the intention of producing exquisite artist-designed furnishings. Not only did they achieve this in spades, but they went on to influence many other design studios and movements across the world (the Omega Workshops in Britain and the Bauhaus in Germany to name just two). When I was researching 1930s fabrics for my MA, it was interesting to see just how many British textile firms were borrowing styles and motifs from the Wiener Werkstätte.

The Werkstätte was active for three decades, during which time it employed nothing short of an army of craftspeople, producing all manner of everyday objects - from cabinets to cutlery, textiles to teapots.

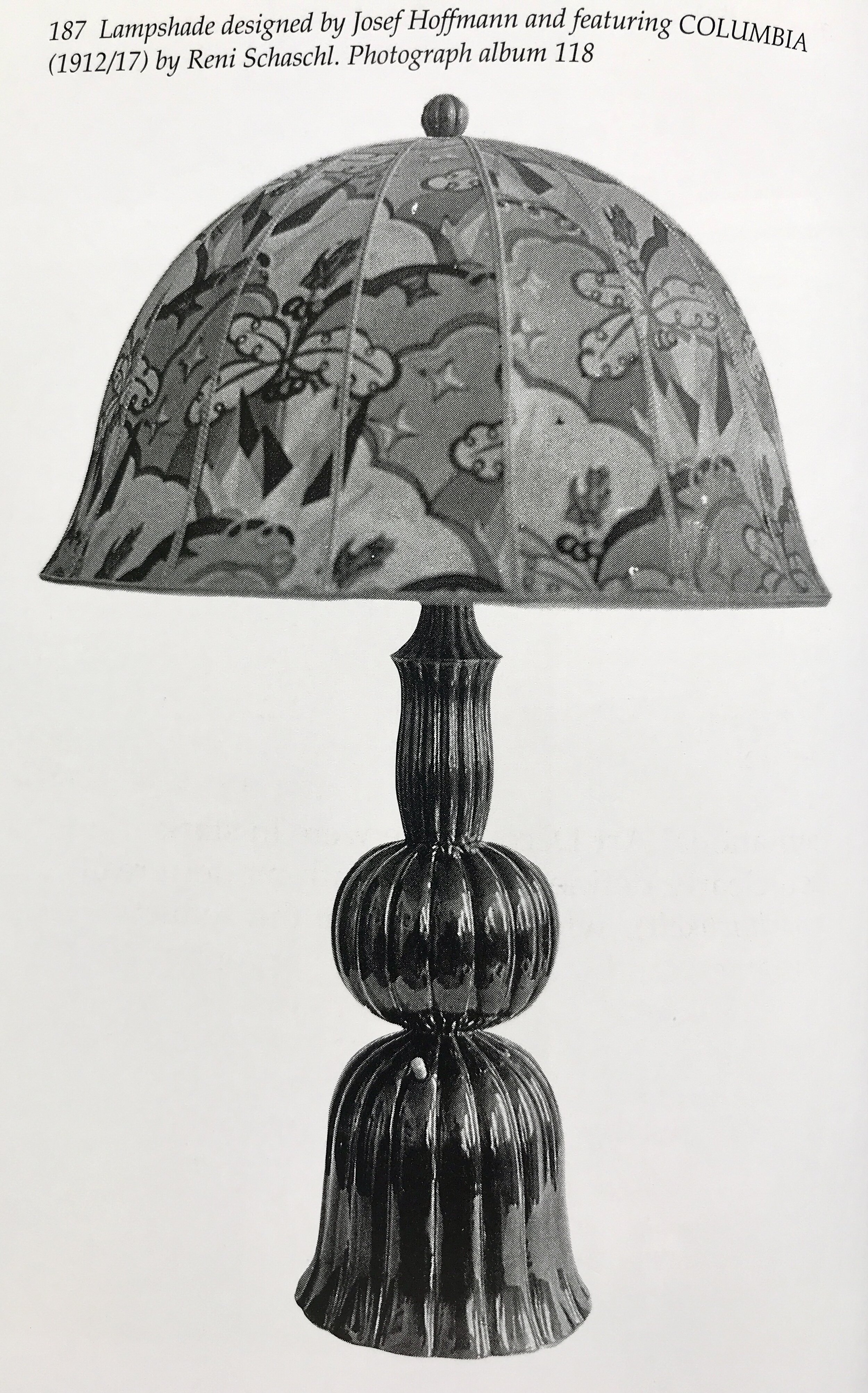

Left: Lampshade feat Columbia fabric by Reni Schaschl, c.1912.

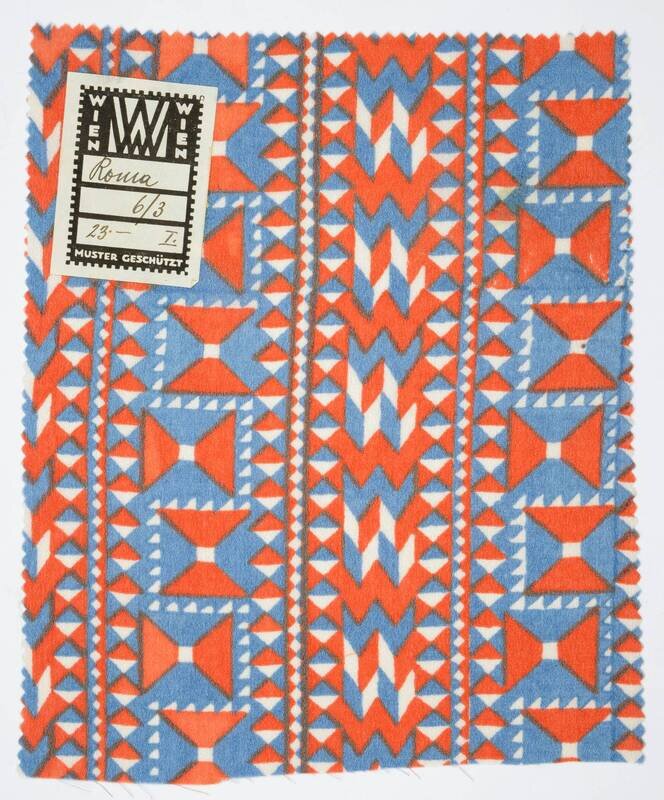

Right: Manissa fabric sample by Max Snischek, 1925-26. Images from Textiles of the Wiener Werkstätte by Angela Völker

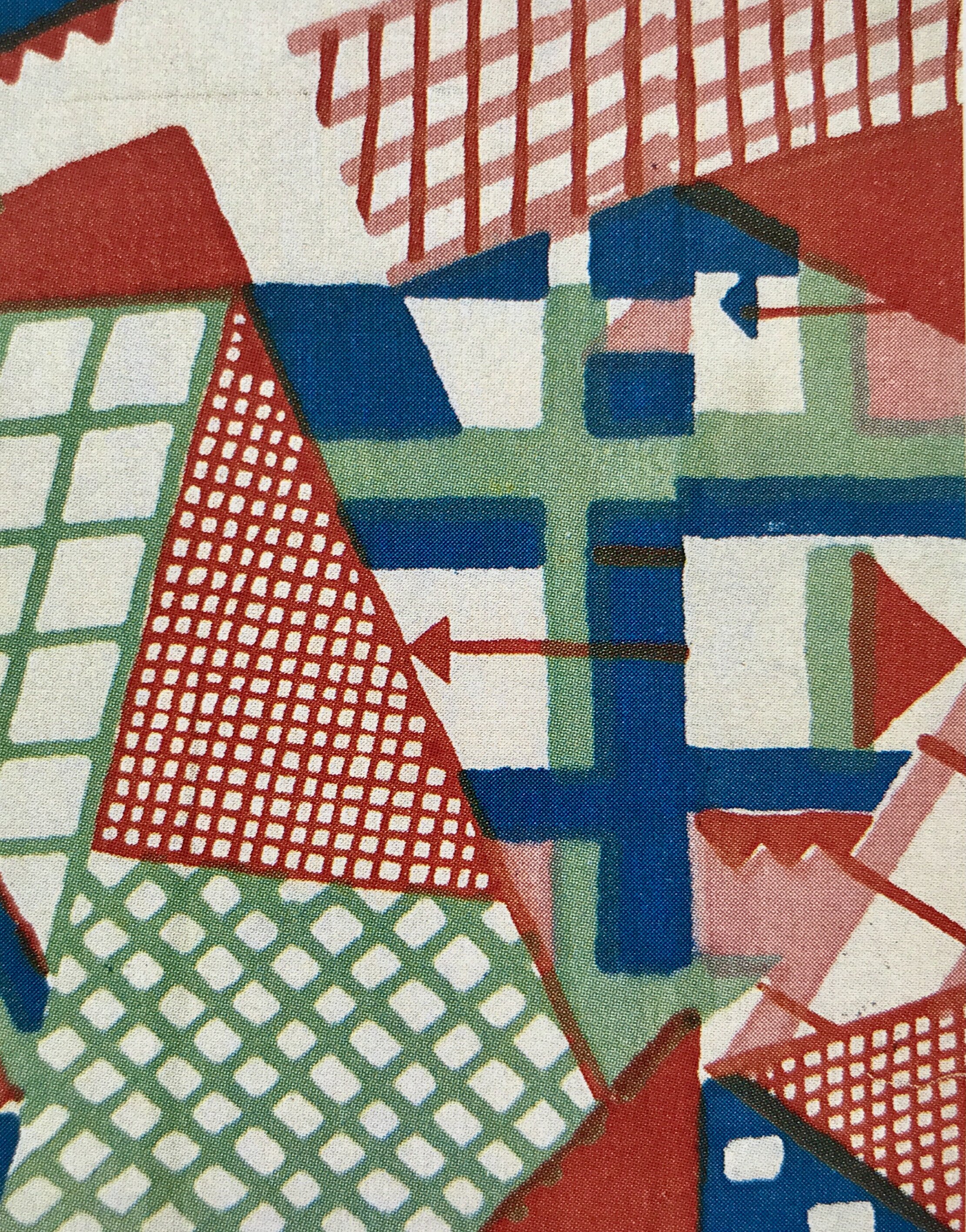

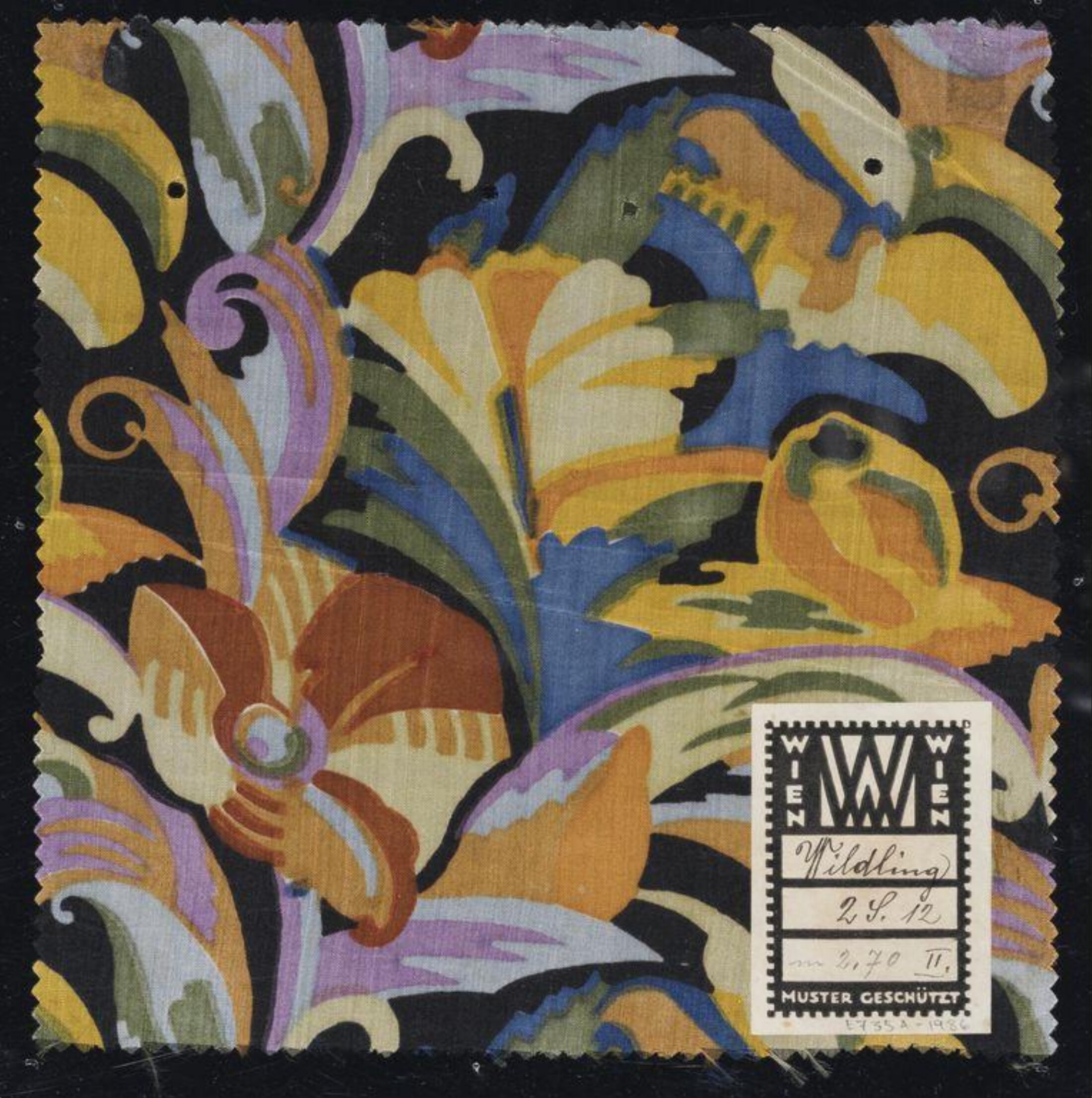

The Werkstätte set up its own textiles department in 1910; between then and 1932 it produced 1,800 textiles by a hundred different designers! Because of its colossal size and the diversity of its designers, there was no fixed Wiener Werkstätte ‘house style’. If you look across their bountiful archive of textile designs, you can see how the patterns range from radically austere to whimsically decorative (and some downright psychedelic).

As Waltraud Neuwirth beautifully put it, their designs were simultaneously “tectonics and movement, classicism and baroque, absence of ornamentation and decorative excess, austerity and ecstasy, monochrome and excessive colour…”

The Werkstätte’s founder and chief overseer, Josef Hoffmann, contributed many textile designs whilst also encouraging young new designers to experiment. Many of the designers were taught by Hoffmann at Vienna’s School of Arts and Crafts and it was a natural progression to go on to work at the workshops.

Waldidyll by Carl Otto Czeschka, 1910-11. Image from Textiles of the Wiener Werkstätte by Angela Völker

Gouache painting for a textile design by Maria Likarz-Strauss, c.1923. Image courtesy of MAK

During the 1910s, the lead designers at the Wiener Werkstätte developed a growing interest in traditional European folk art, as can be seen in some of their most well-known textile designs, such as Waldidyll (pictured above). As design historian Lesley Jackson puts it “they injected new life into traditional floral motifs, giving them punch and zest.”

As the workshops grew, they struggled to maintain their high-minded ideals whilst remaining commercially viable. They encountered recurring financial difficulties, employing a succession of financial directors to try and keep them afloat. It’s for these reasons that the workshops eventually closed in 1932 (many studios didn’t survive the impending war anyhow). The bulk of their collections were sold to the Museum of Applied Arts (MAK) in Vienna, including all the textiles... Oh to spend a week in those archives!

If you're interested in seeing more of their textile archive (without a trip to Vienna), I really recommend Angela Volker’s book Textiles of the Wiener Werkstätte 1910-1932.

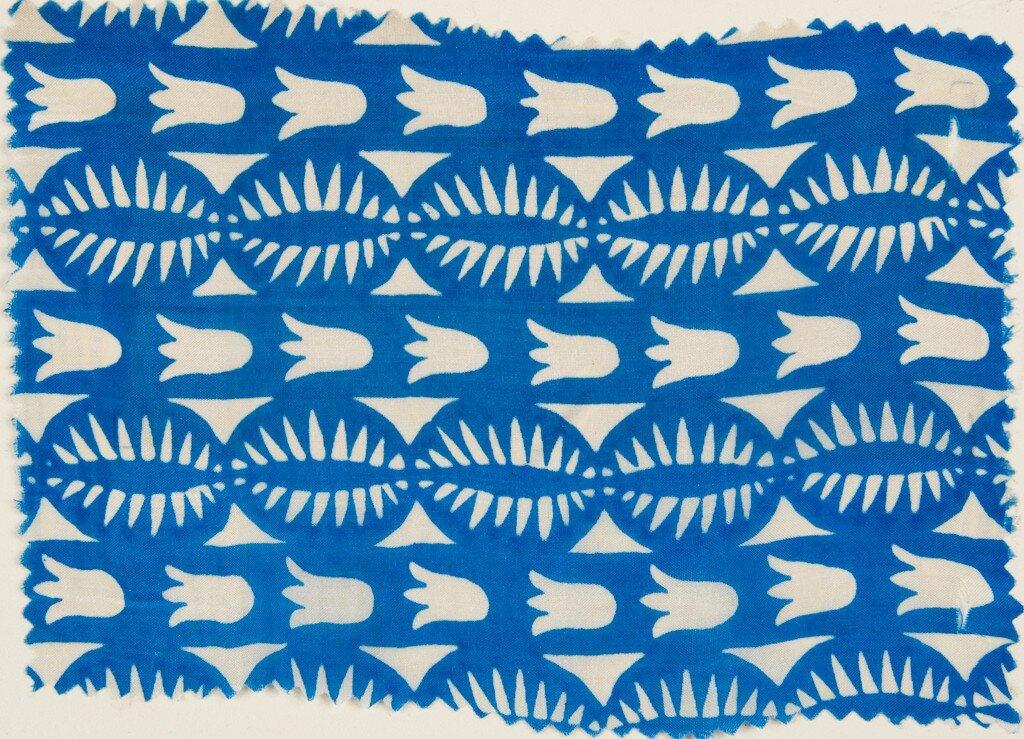

Left: Serpentin fabric by Josef Hoffmann, 1910-15. Right: Wiener Werkstätte fabric swatch, designer unknown